By Matthew Illian, Director of Responsible Investing

By Matthew Illian, Director of Responsible Investing

After a decade of increasing acceptance, the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) movement has faced a political backlash of late, particularly against the “E” goals around the climate crisis. Time will tell whether these are merely temporary headwinds or a devastating storm that could set back climate action efforts. But this can also be an opportunity for investors to gain greater clarity on ESG’s role in responsible investing, and an understanding of what it can – and can’t – do.

By any measure, growth in ESG investing has been substantial over the last ten years. The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment (US SIF) estimates that funds integrating ESG now represent one in every three institutional dollars, or nearly $17 trillion. Attention to ESG can also be measured in corporate earnings calls. FactSet reports that 31% of S&P 500 companies mentioned ESG in fourth quarter 2021 earnings calls. This is up from zero mentions ten years earlier.

ESG refers to business activities that have not typically been measured or reported on financial statements but nonetheless offer important insights into and have impact on corporate performance. This can include climate emissions, industrial disasters, employee satisfaction, supply chain controversies, executive pay and more. Like the ESG movement, reporting on and access to this data have increased significantly in recent years, and today asset managers can easily buy data measuring these and thousands of other ESG factors.

Here’s an example of how these data are used: The war in Ukraine and the disruption in natural gas deliveries have helped spike short-term demand for fossil fuels. With public and international pressure to wind down and recapture emissions from fossil fuel production by 2050 or sooner, ESG investors look for corporations that are prepared for or transitioning toward a low-carbon future. ESG data provide the information they need to help identify firms that are making progress and those that have yet to show any signs of sharing in this work.

But there is resistance to all the ESG data. When Standard & Poor’s gave North Dakota a “slightly negative” rating, describing the state as a “climate transaction risk,” the state treasurer complained loudly. And it is no surprise that attacks on ESG have predominately come from industry groups and political leaders in states where fossil fuel production is a major industry and source of revenue. Texas, West Virginia, North Dakota and Wyoming have all either instituted or are debating bans on ESG investing by state entities, such as pension funds.

These and other states, however, mask their self-interest by framing the argument as the financial elites’ dictating how locals should run their businesses. And they claim that ESG investing increases costs to investors and the public. But there are already data suggesting that the opposite is true. A recent paper by a Wharton School of Business professor and Federal Reserve economist studied the impact of an ESG banking ban in Texas. The authors showed that after the ban went into effect, the state and its municipalities were no longer able to bank with the nation’s largest financial institutions, all of which use ESG factors in their underwriting. The study also found that the ban added between $303-$532 million in extra costs over just eight months. Instead of sticking it to the financial elites, the Texas ESG ban became a self-inflicted wound.

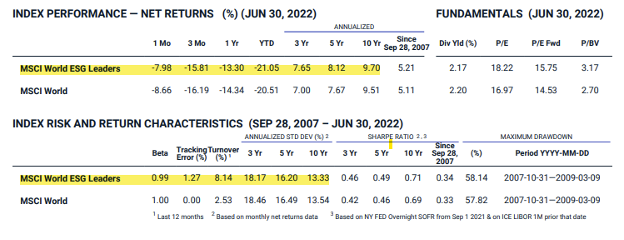

More generally, data also show that investors suffer when ESG is ignored. For example, the MSCI ESG Leaders Index shows that over the last ten years, ESG has helped bolster returns and reduce risk. As of June 30, 2022, the ESG Leaders Index holds an edge over the unaltered market benchmark in 3-, 5- and 10-year returns, and with lower standard deviation over those same time periods. Some will argue that it will take more than ten to fifteen years of data to confirm these trends, but we have at least enough data to quell those who continue to suggest that attention to ESG hurts returns.

Data source: MSCI

Still, there are limitations to ESG data and what ESG investing can do. As MSCI, the largest provider of ESG data, makes very clear, ESG ratings are not a measure of corporate “goodness.” As practiced in the U.S., ESG is primarily focused on helping investors identify and avoid financial risks. This is important to understand when we see that oil and gas companies can receive an “A” on their ESG scorecard even though the entire industry is feeding the climate crisis. The fight against carbon emissions is based largely on voluntary commitments, and until effective laws are in place to protect the atmosphere, top scores will continue to be handed out to the least of the worst greenhouse gas generators. ESG, by itself, won’t cool the earth.

For this reason, at United Church Funds we do not use ESG scoring to shape but rather to support our investment strategy. For our portfolio, we look for asset managers that complement our values, but we do not instruct them to invest only in companies with top ESG scores. ESG data are used to help us identify companies that have the worst social and environmental track records, and we put their stocks on our restricted security list. ESG data are also helpful in our engagements.

For example, when meeting with Dollar Tree management, we considered ESG data that highlighted concerns about pay disparity, benefits and employee safety. Then we prepared for these meetings by speaking with dollar store employees and local labor activists, learning about their numerous and alarming experiences. Although ESG data raised the red flags, it was the personal accounts that fleshed out the numbers and moved us to act. You can read examples of published accounts here and here.

ESG may have its opponents, but there is no question that it has spurred an important evolution for the investment industry and will continue to be a driving force. At the same time, it will never be a proxy or substitute for the values that we hold and the priorities we place on justice for all people and the planet.