By Matthew Illian

Sustainable investing strategies have been hotly debated throughout the investing community. In recent weeks, that debate has reached something of a fever pitch as high-profile journalists and spokespersons from major financial publications have come out either on the attack or in defense of responsible investing.

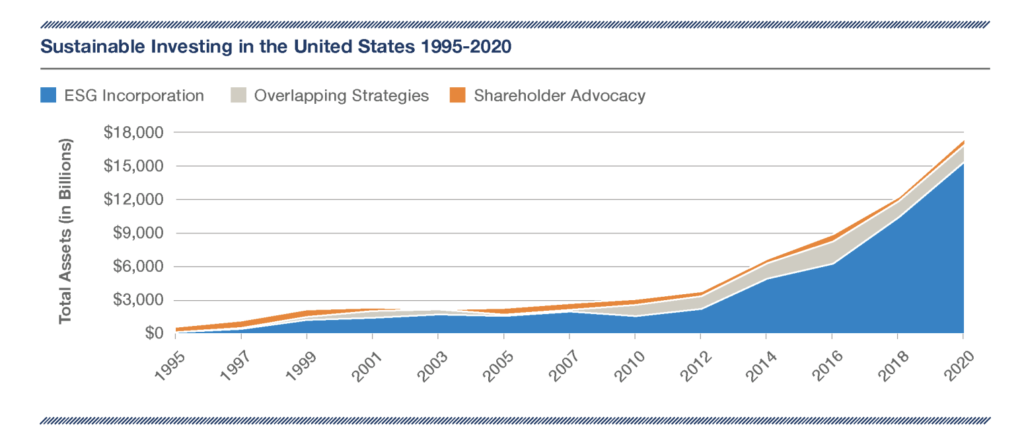

No one will deny that sustainable investing has grown substantially. The U.S. Sustainable Investment Forum has reported that over the last 25 years, there has been a 25-fold increase in the amount of assets held under a sustainable investing mandate.

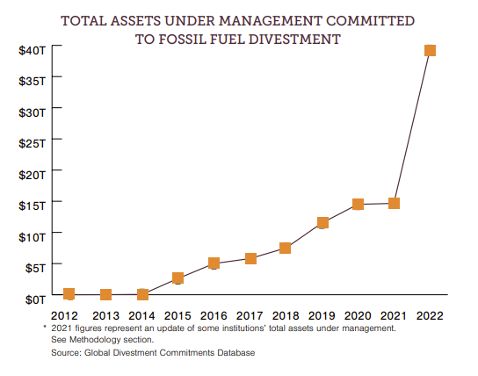

An example of the spectacular growth in sustainable investing is the fossil fuel divestment movement, which was once considered a radical decision by faith and environmental groups and is now embraced by leading universities, endowments, pensions and sovereign wealth funds. The Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Commitments Database reports that while the first three years of the campaign netted 181 public commitments, the most recent three years have seen 485 new commitments. Total assets under management of institutions committed to divesting from fossil fuels is now up to nearly $40 trillion.

Throwing cold water on the sustainability movement is columnist James Mackintosh of The Wall Street Journal who claimed in a recent series of articles that responsible investing is a “craze”; that investors are being “virtue duped”; and that this will cost them in the long run. His generally misguided argument is summarized as follows:

- While attending to ESG (environmental, social and governance) factors may have been fruitful in the past, all the low-hanging fruit has been picked and future improvements will be costly to the bottom line and to investors.

- If there are any outstanding ways to profit from ESG factors, pursuing this path isn’t virtuous but rather just part of regular profit-maximizing. (So don’t feel too good about yourselves.)

- Divesting from bad stuff (e.g. coal mines) does nothing to make the world better because someone else will buy them. There are still lots of profits to be made in fossil fuels.

- Attempting to change corporate practice through sustainable investing is a distraction from the simpler and more effective approach of maximizing social utility through the government’s powers of taxation and regulation. In other words, the private investor sector has no business attempting to make the world a better place.

In a scathing retort, Jon Hale, Global Head of Sustainability Research at Morningstar, argued that Mackintosh is missing the big story here, which is that there has been a shift in economic awareness and cultural expectations. He describes this shift as a movement away from “shareholder primacy,” in which profitability is the holy grail, to “stakeholder primacy,” which involves a much broader set of responsibilities to employees, local communities, investors and the climate at large. Hale argues the following:

- Government action (taxation and regulation) is not a simple approach, and anyone who argues as much is naïve.

- Investors can invest sustainably and promote good social and environmental policy at the same time (the “walk and chew gum” approach).

- Shareholder engagement, whereby shareholders use their influence as owners, is a very effective way to communicate with management.

Here at UCF, our view is that Hale has outlined the correct approach, but he doesn’t go far enough in promoting the value of shareholder engagement. Shareholder engagement – leveraging the power of investor voice – isn’t just an effective addition to sustainable investing; it is integral.

Those faith and values investors who are old enough to recall the protests against apartheid in South Africa will remember how these efforts to pressure banks and other corporations to divest from the region helped bring about vital reforms. The late Archbishop Desmond Tutu himself thanked many of these investors for their commitments.

Shareholder engagement is needed just as much today. This is why we continue to file shareholder resolutions like the one we filed at Meta to increase their transparency around lobbying. This is also why we support and partner with colleagues at the Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility (ICCR) to push companies to take responsibility for human rights abuses that are taking place throughout their supply chain. We partner with ClimateAction 100+ to pressure the world’s most prolific carbon emitters to set science-based net-zero goals that are backed up by demonstrated action. Through these organizations, we join scores of other asset managers that are able to accomplish what no one organization could accomplish on its own.

To be fair, not all sustainable investing strategies are created equal. Those strategies being dubbed as “light green,” which fail to use the entire toolbox of responsible investing, may rightfully be accused of greenwashing or virtue duping. For example, Deutsche Bank AG’s asset-management arm, DWS Group, is under investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and federal prosecutors for allegedly overstating its ESG credentials across its $1T fund lineup.

But the bottom line is that UCF believes in the power of responsible investing, and we remain committed to using our investments to create a just world for all. We will continue to work with those who are raising the standards on what society can and should expect from business. And we will continue to dispel those myths that distract investors from this work. Onward we go!